The Violin Music of East Germany Part II: Kurt Schwaen

This post is the 2nd installment of my GDR music project research. Over the past few months, during this era of social distancing, I have done quite a bit of research and score collection for this project. I have found many names and scores, many rabbit holes to jump down and treasure to hunt. As always, with research, you uncover more questions than you do answers, but that's just part of the game. I haven't come out completely empty-handed, though. Thankfully, some scores are not impossible to find, and I will be highlighting some of those people and their work here.

In my preliminary research about the composers and pieces written in East Germany, Kurt Schwaen's name is one of the most readily available. Before starting this project, I didn't know the name at all, and I'm guessing several of you are equally as unaware (but bravo if his name is already in your library). There is a website devoted to Schwaen's musical career that is updated and curated by Dr. Ina Iske-Schwaen, but this is certainly not the case for most East German composers. It has added to the ease and simplicity of finding and collecting some of his scores.

To clarify: I'm most interested in finding violin music written between 1949-1989, including solo works, concerti, sonatas, and works for small chamber ensembles (quartets, piano trios, duos, etc.). Many composers wrote works before and after this period, and I will probably end up collecting many of these scores too. Below, you will find a list of compositions found on various sources online. I have noted which ones I have successfully obtained at the time of writing this.

The following is a little bit about Kurt Schwaen and his music.

b. June 21, 1909, in Katowice, Poland (under Nazi occupation during WWII)

d. October 9, 2007, Berlin, Germany

From 1929 to 1933, Schwaen studied musicology, art history, philosophy, and German at the universities in Breslau, Poland, and Berlin, Germany.

In 1930 he met Hanns Eisler (more on him later) who greatly influenced his compositional style. After becoming active in an anti-fascist student group, he joined the Communist Party of Germany, and from 1935 to 1938, and he spent time in prison because of his political views. After his release, Schwaen found enduring inspiration from his work as a pianist with renowned dance soloists in a studio for expressive dance in Berlin.

After the war, he returned to Berlin. He spent much of his time working to rebuild the musical culture of that city by writing compositions for amateur music groups, choirs, music schools, and chamber ensembles. After the end of World War II, which Schwaen survived in the Penal Division 999, he found ample work in the rebuilding of the public music schools and as musical advisor to the German Volksbühne Theatre.

Between 1953 and 1956, he worked with Bertolt Brecht, who had a profound impact on his future compositions. He worked with Brecht from 1953-1956. In 1961 he became a member of the DDR Akademie der Künste, where he was head of the music department from 1965 to 1970. From 1962 to 1978, he was president of the East German National Folk Music committee. Between 1973 and 1981, he directed the children's musical theatre in Leipzig.

Schwaen has held numerous honorary positions, including being named an official member of the Association of Composers and Musicologists, the Academy of Arts in 1961. In 1983 he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Leipzig University and received several other state awards. His compositional output, which spans seven and a half decades, contains more than 600 works in every genre, from song and chanson to choral music, piano works, chamber music, and orchestral works, and includes opera and works for the ballet.

Schwaen later settled in Berlin-Mahlsdorf, where he died at the age of 98. His widow, Dr. Ina Iske-Schwaen, maintains an archive dedicated to his works in his Mahlsdorf home.

There are a couple of great quotes from Schwaen on his website that I enjoy:

Everything easy is unusual.

Everything easy is unusually difficult.

I am for shortness.

But shortness because you choose no length, not because you are not able to.

Compositions applicable to my project:

· Piano Trio No. 3 for violin, violoncello, and piano (1982)

· Suite Classique (Classical Suite) for violin and piano (1980) ACQUIRED

· Piano Trio No. 4 for violin, violoncello, and piano (1983)

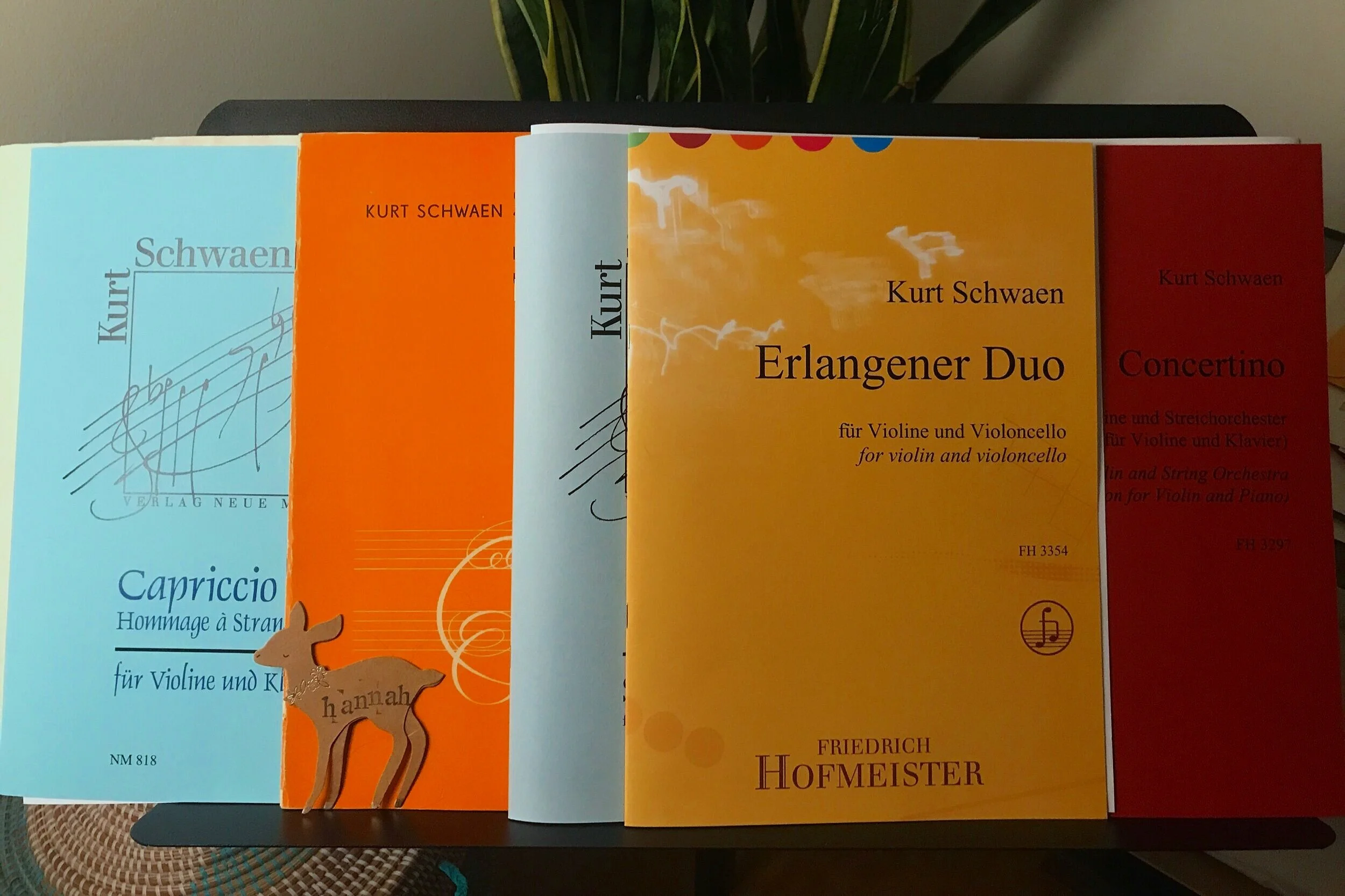

· Capriccio. Hommage à Strawinsky for violin and piano (1986) ACQUIRED

· Sequences in Es-flat. Four movements for violin and piano (1996)

· Piano Trio No. 5 – »en miniature« for violin, violoncello, and piano (1987)

· Serenade for Solo Violin and 3 Solo or Tutti Violins (1998)

· Violin Concerto KSV 433 (1979)

Pieces Not listed online, but (somehow) acquired:

· Concertino for Violin and String Orchestra (1971) ACQUIRED

· Sonatine for Violin and Piano (1951) ACQUIRED

· Erlangener Duo for Violin and Cello ACQUIRED

A little about some of the music listed above:

In the Suite Classique (Classical Suite) for violin and piano, Schwaen consciously employs traditional form to organize this piece. Of course, he uses this model for his unique purposes in the formation of different movement characters. The outer movements are determined and virtuosic, whereas the inner ring, which frames the unrestrained third movement, are more »cantabile«. Whether calm or active, tense or relaxed, powerful or floating and light, complicated or simple – Schwaen writes with a compelling musicality.

These traits also apply in the case of the Capriccio for violin and piano. Written for the same instrumental combination, Schwaen here channels his intention toward the presentation of a particular genre, an »Hommage à Stravinsky«. The role model function of this master is well-known. Schwaen even spoke of influence. This work is built on formula-like circular, short repetitive motions. It presents itself dancingly light, even playful. A melodic, at times improvisatory sounding middle section allows the »capriccioso« to come to the fore, especially clearly.

Surprisingly, considering how easy – relatively speaking – his violin music was to obtain, there are very few recordings of his music available online. I checked Youtube, Vimeo, Spotify (there is only one album of simple pieces with German introductions), Amazon Music, Apple Music, and Soundcloud. One recording that I did find and enjoy is this recording on youtube of his Concerto Grosso for String Quartet and chamber orchestra.